- Home

- Clay A. Johnson

The Information Diet Page 9

The Information Diet Read online

Page 9

You can also increase your social time, spending time talking with your spouse, family, and friends. Another good use of your time is giving your mind a chance to digest the things that you’ve read by taking long walks, spending time exercising, or even meditating.

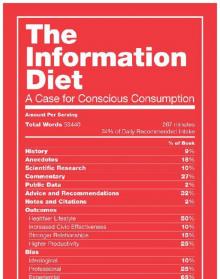

Nutrition isn’t just about what or how much to eat, it’s about eating balanced meals. Just like the new recommendation graphic from the government recommends that our plate consist of 30% grains, 30% vegetables, 20% protein, and 20% fruit washed down with a glass of milk, we’ve got to come up with a healthy means of consciously consuming information.

Unfortunately, we can’t make an exact replica of MyPlate.gov for information—we don’t have the kinds of neurological research out there to figure out what a healthy, complete diet truly looks like. But like Banting, we do know the kinds of things we ought to consume less of.

Mass affirmation is the refined sugar of the mind—I’m not talking about the kind of relatively rare positive affirmation you get from friends or family, telling you that you’re loved and respected. Rather, it’s the mass affirmation: the affirmations you get that aren’t intended for you specifically, the stuff that television is best at, but also permeates through all of our information delivery mechanisms. The suppliers that make a living telling you how right you are are the ones you ought to avoid the most.

I try to limit myself to no more than 30 minutes a day of mass affirmation, and strive to consume much less. It means making some tough choices, and letting go of some things you might enjoy. At a maximum of a half-hour a day, for some liberals, it means having to make the dreaded decision of choosing between Stephen Colbert, Jon Stewart, and a regimen of DailyKos. For the conservative, it may mean having to pick between Fox and Friends for a half-hour in the morning, and a half-hour of Bill O’Reilly in the evening.

Consume Locally

The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy (Del Rey) by Douglas Adams starts off with the book’s protagonist, Arthur Dent, having his flat completely demolished by a local government agency, thanks to an eminent domain ruling to build a highway through his apartment building. The notice, it’s written, was to be found in the bowels of a government building, up for “public display.”

Perhaps Dent was too obsessed with US Weekly, or news from far away. Our obsession with national news over local news has to end. While it’s important to stay abreast of national and world affairs, most of us give too much weight to information that’s not actionable and relevant to our daily lives. There are more dealers of junk, more profits involved, and more lies to be told as we sit higher on the trophic pyramid.

A healthy information diet means the avoidance of overprocessed information. A healthy information dieter constantly tries to remove these junk dealers from the consumption chain. That means either consuming locally or working consistently to remove distance to the things that you investigate.

Consuming low on the metaphorical trophic information pyramid doesn’t mean just sticking closer to the facts; it also means that it’s easier to stick close to the facts when you stick close to home. The further away from home you get, the more attention you have to pay to how many operators have been involved in getting you that information.

Facebook’s founder, Mark Zuckerberg, once quipped, to the alarm of many an activist: “A squirrel dying in front of your house may be more relevant to your interests right now than people dying in Africa,”[84] and while I too bemoan the trivialization of famine, genocide, and HIV—he has a point. You alone can go get the squirrel and clean it up and prevent your neighborhood from smelling like dead animal. Chances are, you’re unable to solve famine, rid the continent of Africa from evil warlords, and cure HIV all by yourself. Local news is more actionable and relevant to the individual than global issues.

Luckily, there’s a renaissance going on in the world of local news—new tools allow you to get online and see news and information down to the narrowest geographic criteria possible: your block. Today, major cities and government agencies are releasing information by the gigabyte that informs us on the real goings-on in our neighborhoods.

If you’re in one of the dozens of cities lucky enough to be covered by Everyblock, I highly recommend it as an important daily source of information. The site aggregates dozens of data feeds that come from local governments and turns them into an easy-to-read, relatively opinion-free way of seeing what’s going on at the block level—and you’d be surprised how much information there is about your single block.

Everything from bulk trash pickups to police reports to photos taken in your neighborhood to recent real estate listings are available for you. You register for the service, plug in your address, and tell the service whether you are interested in getting information about your city, your neighborhood, or the area within an eight-block, four-block or even one-block radius of where you live.

The site also allows you to post messages to other people in your neighborhood so you can talk about the issues affecting your real, local community. It makes the information that comes out of your community immediately actionable, and allows people to connect with their neighbors easily.

Beyond Everyblock, your city may have its own data catalog available for you to peruse. Most major cities—like D.C., Portland, Seattle, San Francisco, and New York—have them, and more are on the way. To find yours, do a Google search for your city’s name and the phrase “data catalog” and you’ll likely stumble upon it. If you cannot find one, try searching for the email address of your local government’s CIO (Chief Information Officer), writing to them, and asking them to make the data feeds that they have available online.

Public data is your data—you fund its collection with your tax dollars, and it ought to be taken out of the silos in the underbellies of city halls across the country, and into the light of day. Most sunshine laws—laws that require governments to respond to citizen requests to be open—require government officials to respond to citizen requests for information. Be an activist, and ask for its release.

It’s hard to be factually incorrect about this kind of data, and reading about parking in your neighborhood may seem quite dull. Over time though, you’re able to spot trends: observing a string of car thefts on your block may yield you some pertinent information—certainly more pertinent to your safety than whether the federal government is going to invest in high-speed rail.

For news, reading your local paper, watching your local news when it’s on, or reading local blogs isn’t a bad idea, but keep in mind: you’re now becoming a secondary or tertiary consumer of information, and you’re more subject to succumbing to your own bias and other forms of misreporting.

While this information is less likely to be as manufactured as what you’ll find in the national and international news, it will still require some work in order to make sure it’s trustworthy and verifiable. In order to consume this information safely, you must do the extra work of investigating source material, figuring out the intent of the person delivering that information to you, and determining that information’s effects on you.

The local news renaissance is also a renaissance in specialized, deep wells of information. Instead of grazing on global and national news, and information about people you don’t know and who don’t care about you, shift your information consumption to local news and people who do care about you. Try to achieve deeper relationships with the information you’re consuming: if you must consume information about the affairs of people and places far away, try slicing off a niche, and developing a mastery of it.

But geographically local information isn’t the only kind of local information we can get to. Socially proximate information also sits near the bottom of our informational trophic pyramid. Like geographically local information, socially local information—information about the people closest to us—is actionable, relevant, and important to our connections with other human beings.[85]

The Web gives us new ways to check in on those we know and love, even when they�

�re far away. But like all other forms of information, social media comes with consequences. We have to filter the information that our friends are sharing about themselves and the information that they’re resharing from elsewhere.

It’s good to fine-tune your lists of friends and acquaintances and fortunately, all of the major social networks give us this ability. Facebook’s groups and lists, Google+’s circles, and Twitter’s list functionalities make it so that we can sort our friends and view our social networks through the lenses of what’s important.

If you are a user of one or more of these services, take an hour or two and sort through your lists of friends. Create a group, list, or circle for family members, another for close friends, another for work colleagues, and another for people you’d like to get to know better, and read those posts consciously during set periods of the day, rather than plunging yourself into an ever-growing stream of incoming media that your brain will be unable to resist.

Low-Ad

We’ve adjusted our information culture such that we now expect information to be free to the consumer. But that free information comes with a much higher cost: advertising. A healthy information diet contains as few advertisements as possible. The economics of advertisement-based media make it so that our content producers must draw eyeballs in on every piece of content, and that results in sensationalism.

Sensationalizing content tends to degrade its quality. That’s not the only cost, though: because advertising persuades us, over time, to buy things that we wouldn’t ordinarily buy, the cost of consuming ad-supported content is higher than we think. I know I’ve ordered a pizza or two from my local pizza joint after watching a television commercial for Pizza Hut.

The reality is that so much of our information—even information we pay for—comes along with advertisements, and it’s nearly impossible to escape advertising completely. Our routes to work and our walks down the street are filled with advertising, and even if we manage to escape those, our trusty letter-carrier delivers more directly to our homes for us to see.

Part of a healthy information diet is respect for good content, and a disrespect for advertisements. We have to reward our honest, nutritious content providers with financial success if we’re going to make significant changes. I subscribe to ConsumerReports.org and NationalGeographic.com as a paying member because they provide good, high-quality, and mostly ad-free content to their subscribers.

A healthy information dieter most certainly won’t sign up to receive advertisements—though many of us do. Our email boxes are filling up not just with spam, but with the latest travel deals from Expedia and specials from JC Penny and Amazon.com. Unsubscribe from these lists, or create a filter or rule in your email client to remove them from your inbox.

While it’s likely impossible to be informed and ad-free, it ought to be something to strive for. To limit your exposure to advertising alongside content, I recommend using tools like Readability.com. Readability gives you the ability to remove distraction from content—it removes advertising completely from any article you’re reading, gives you a more readable typeface, and adjusts the width of each article to make it easier to read.

Readability incorporates another application called Instapaper in its service. It is a similar tool that also allows you click a button on your web browser and move the article to your mobile device. With Instapaper, you can find articles you’d like to read, and read them more easily and more free from the distractions of advertisements and suggested reading headlines on your iPad, iPhone, or Android device, or through Instapaper’s service on the Web.

Knowing that they’re circumventing the current advertising distribution model of information, Readability charges a minimum membership fee of $5.00 per month that you can increase to however much you want. It takes 30% of the membership fee as its own, then allocates the remaining 70% to the content providers that you read through the service. It’s an invisible, transparent way to support content providers without having to wade through advertisements.

The websites of all content providers are designed to keep you reading, and to expose you to the most advertising impressions possible. It’s why they split articles up into several pages, and why when you scroll down to the end of an article, you’re plied with more enticing articles to read.

Instapaper and Readability help to reduce your exposure to these time-sucks, and help you retain a sense of conscious consumption. The key part of these tools is that they make it easier for you to focus on what it is that you want to focus on, and eliminate the distractions you’d normally encounter. They make conscious consumption easy—instead of blindly surfing the Web and reacting to what’s being thrown at you, you can instead shop for content, select the things you want to read, and then have a longer reading session free from distraction.

Diversity

Processed information isn’t the only thing to avoid. If we are comparing an information diet to a food diet, then affirmation of what you already believe is the mind’s sugar. A healthy information diet means seeking out diversity, both in topic area and in perspective.

A healthy information diet means affirming our beliefs only to an extent, keeping a watchful eye on our own fanaticism, and soaking up as much challenge to our beliefs as we possibly can. Getting perspectives that agree with you is one thing, but getting only perspectives that agree with you is bad for you—it may limit your exposure to good information and may cause you to suffer from the forms of ignorance I described earlier. Moreover, it’s through having your ideas challenged (and through the synthesis, analysis, and reflection of those challenges) that your ideas get better.

Fried chicken and ice cream are okay to eat every once in a while—at most, a few times a year when you’re celebrating or feeling particularly down and just need some comfort food. The same goes for the news sources that provide you with the most comfort and information, or even antagonize you. Recognize them as primarily entertainment, and treat them like rare, special servings rather than as something representative of your daily intake.

Striving for synthesis is necessary, and that means actively encouraging a diversity of opinion at all levels of your information diet. Remember the story of Eli Pariser and the filter bubble: we never want a personalization algorithm to start thinking that we’re only interested in hearing viewpoints from one particular side, one particular class of people, or one particular topic or issue.

Asynchronous social networks (ones where you can follow someone without them following you back) like Twitter and Google+ allow you to craft a diverse set of information inputs. You can choose to balance your inputs by following people with a different background or point of view than yourself and your closest friends to get a better perspective, or to learn where people who are different than you are coming from.

Without constant attention to perspective diversity, we assure ourselves mutual intellectual sycophanticide. Because human beings tend to self-select into self-reinforcing groups, tools like Facebook and Twitter allow us to get not only constant updates from our friends, but also constant affirmations of our beliefs. Only through constant pruning, selection, and conscious clicking can we make them work for us.

In other words, the only thing to be fundamentally opposed to is fundamentalism itself. To help counter this, I keep a bias journal on my computer, but you could just as easily have it written down on paper if you like. In it, I keep my firm positions and values—stuff I find to be absolute. It’s just a simple, noncategorized list of strong biases I may have. Here are some of mine:

Affordable access to quality healthcare is a fundamental right

Innovation in the private sector will always outperform innovation in government

Large organizations are less interested in the individual than small ones

Strong affinity for Google products (could be because I get invited to speak at their conferences)

Strong affinity towards technical solutions for social problems

Me

n who wear brightly colored Pumas are annoying

Some biases are stronger than others, of course, but what’s important is that you’re honest with yourself about what your biases are. Some of them could be deeply private, but you don’t have to share your list. What’s important is that you keep the list, are explicit about it, and constantly look to find data and people that challenge your biases—and prescribe yourself enough time to encounter them.

It’s also important to seek out diverse topics of information, as the synthesis of information from different fields helps us create better ideas. It also helps keep us from losing our social breadth—so we have more to talk about than the specialized knowledge of our particular fields. Introduce some new ones into your information diet. I find three resources particularly useful in this regard.

The first is the Khan Academy. Started by Salman Khan in 2006 in order to tutor his young cousins, the site now features over 2,600 small lectures on anything from basic subjects like arithmetic and European history to advanced subjects like organic chemistry, the Paulson bailout, and the Geithner plan to solve the banking crisis.

Being an infovegan means acquiring the basic knowledge you need in order to understand what the data is telling you. The Khan Academy opens the door and lets you in. It’s not a good stopping point, but it’s an excellent way to pick up the basics of a subject that will give you the knowledge you need in order to conduct further research.

The second is TED (Technology, Education, and Design), an organization that puts on a conference every year. It invites luminaries from a myriad fields to come and present what they’re working on, and then share the talks online via its website. TED talks—especially about things you’re not ordinarily interested in—are a great way to add diversity to your diet.

The Information Diet

The Information Diet